Creative pursuits at God’s service can make a man’s heart sing, but they’re just as likely to make him beat his head against a wall. They’re plagued with doubts, with false starts, with curses and prayers, and with a fear and sense of failure that seldom come with secular work.

I thought God wanted me to do this. Was I wrong?

It’s enough to make a man quit in a fit of artistic pique. But Father Philip wasn’t so easily deterred.

Considering the scope of his plan, that was a miracle in and of itself.

It was a big plan for a big problem. Simple in theory, but when do simple plans ever stay that way? With God on his side, Philip had faith that things would work out, but it was comforting to know he also had earthly help.

He had a bunch of weird friends.

Unknown Artist

A Strange Plan Requires Stranger Friends

Rome in 1553 was in a bad state. A Christian nation? That was a thing of the past. The city was Christian in name, but in practice, Rome had traded the Bible for Bacchus and returned to its pagan ways. Adultery ran rampant. Cardinals glutted themselves on wealth and excess. Rome took its values lightly and its vices seriously.

So Father Philip decided to do the same. Holiness, after all, was a much lighter burden to bear than sin’s chains.

Reformers who had come before Philip thought to solve the problem with fire-and-brimstone preaching, but some unexplainable glimmer in his heart told him this wasn’t quite right. He had a different idea, one that won him his share of critics. Their discouragements, plus the creative turmoil that surrounds innovation, might have stopped him…if he didn’t have friends.

Because his friends? They were just as crazy as he was. And together, they would make sure his hare-brained scheme got off the ground.

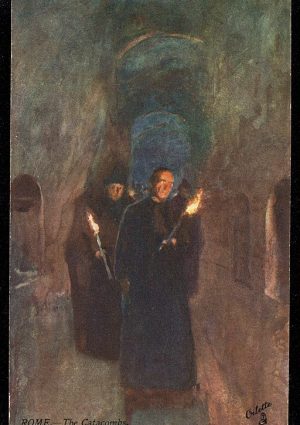

Or went underground, as the case turned out to be.

His idea? Counter one of Rome’s most popular entertainments with a city-wide pilgrimage that started in the catacombs. This might sound eerily entertaining to today’s crowds, but the Renaissance Romans were more interested in living it up with the, well, living than in chilling with the dead. It was an ironic place to begin his pilgrimage, but the irony didn’t stop there. After the catacombs? They would start singing.

As they walked to the next stop on the road. But still.

After that? They’d watch a performance and eat lunch before heading for another church. They’d sing some more along the way, and someone would tell a joke or two. (It would probably be Philip; he carried a book of jokes everywhere he went.) All in all, they’d visit seven churches. And sermons denouncing vice? They wouldn’t hear one.

It was a weird way to combat hedonism and bring souls to Christ.

But it worked.

The first ragtag pilgrimage boasted about 20 companions, but as time passed, Father Philip’s pilgrimages amassed thousands. Forget mocking music and bawdy ballads on the streets. When the pilgrims went by, their deafening songs and laughter rattled through every alley and byway. Bystanders would cry out in greeting and wave as they went past. The same Romans who sneered at sermonizing priests adored Father Philip–and many of them abandoned the path of sin to follow in his footsteps instead.

All because of one man’s idea…and because of the support of his friends.

Who were these friends of Father Philip’s who helped him put on those pilgrimages and encouraged his plans? Who were these crazy men who saw the world and God’s truth in the same light and mirth and color he did?

And what do they have to say to us today?

Something about art’s power to evangelize, yes. But also something about the power of friends.

by Giovanni Battista Piazetta

Holy Pranksters

The world today knows Father Philip as St. Philip Neri, “Second Apostle to Rome,” founder of the Oratorians, and patron of humor and joy. But to that small group of friends who helped Philip create a pilgrimage and then the Oratory, he was the guy who once showed up to a party with half his beard and moustache shaved.

To his friends, Philip Neri wasn’t a lofty saint in the sky. He was a man like them–eating with them, praying with them, debating with them, and getting one of them nearly thrown out of a wine shop by sending him on a prank-filled wild goose chase. They wanted to throttle him half the time, but they couldn’t. They were too busy laughing.

St. Philip Neri and his friends saw the world in a different light. They saw truths about God that others did not, and they wondered about truths that no one else thought mattered. That, after all, is what it means to be friends–according to C.S. Lewis, at least. If men are made in God’s image and likeness, we resemble each other because we resemble our Creator. But we will resemble a friend because we were formed not just of God’s own life, but breathed into existence–so it seems–within the very same breath.

What is a Friend?

To find a friend is to find someone who sees a truth you can see which others can’t. It’s like seeing the color blue together when the rest of the world only sees red. When you find that friend, you’re speechless. It’s nearly impossible to believe, and the experience is as euphoric as discovering chocolate cake when you bite into what looks like liverwurst. It’s a shock to the system, an impossibility of delights. You might not need blue, friendship, or chocolate cake, but they make everything as bright as diamonds, like when Dorothy leaves her tornado-wrecked, black-and-white world and steps into Oz with all its color and life.

“Friendship,” says C.S. Lewis in his book The Four Loves, “is unnecessary, like philosophy, like art, like the universe itself (for God did not need to create). It has no survivial value; rather it is one of those things which give value to survival.”

Necessary? Maybe not. But beautiful? A treasure ten thousand-fold? Yes.

But a treasure for whom?

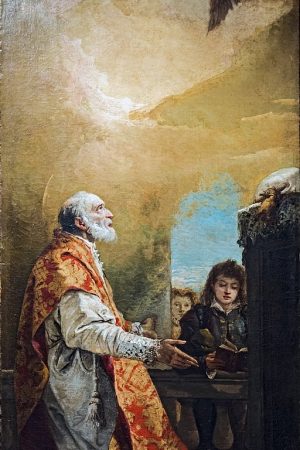

by Giandomenico Tiepolo

Pious Pursuits and Wild Goose Chases

Baronius should have known better than to take advice from his mentor and friend Father Philip. (Let us not forget the debacle he endured in the wine shop.) But he did know better than to ignore Philip’s advice about the work he should pursue. Because Philip had a knack for being right.

As friends, Baronius and Father Philip saw God and the world He made in a way others did not, but only Philip had an eye for how each friend’s gifts fit into the service of the truths that bonded them. Baronius wanted to light Rome on fire with his lectures on morality, but Father Philip set him to lecture on Church history instead.

And to teach the same series of lectures seven times.

It doesn’t sound very creative. But there was a method to Father Philip’s madness–and a surprising level of insight about editing’s importance for a man who wrote so little himself. When you teach and write the same material seven times, you get pretty good at it. You know it well enough to pick out where your research has holes, where your logic needs to be shored up, and what you need to do better to make your audience understand.

Baronius’ wild goose chase in the wine shop was more than a riotously good story. It was a training ground for the chase after forgotten history that he would follow for the next twenty-three years. Though he originally had no interest in history, it soon became his passion, because Father Philip’s wisdom in choosing history as Baronius’ quest illuminated more clearly the truth they both sought. Rome and indeed the world needed virtue’s lightness–and needed to cast off vice’s chains. Baronius’ Church history lectures were to be the weapon for breaking those chains.

But what was the sin he would battle? It was the scourge of the Renaissance and the divide that still separates Christ’s people today. The battle was with Protestantism itself.

This battle that Father Philip provoked for the young Baronius would follow him through his pre-ordination years, his time building up the Oratory, and his own elevation–following Philip’s death–to head of the Oratory, Confessor to the Pope, and Cardinal of the Church. Those lectures would become a book that went head-to-head with the propaganda-riddled Church histories Protestants peddled throughout Europe. From the wine shop to the podium to the pen and the page, Father Philip’s friendship not only made Baronius a better man–one worthy of the title Venerable he bears now–but it gave the world the first great history of the Church, one that’s still relevant today.

What Makes Friendship a Treasure?

Friendship is a treasure, yes. It’s a treasure to those who find themselves within that friendship, but it’s also a treasure to the world in the good that it fosters for all mankind.

Only virtuous friendships do this. Friendships can affect society for good or bad. When a friendship is rooted in God? It may not have survival value, Lewis says–not in the physical sense. But it can help souls survive this world’s attempts to kill them. Its fruits can help others–and the friends themselves–live not for this world, but for the one to come.

But that’s not all virtuous friendships can do.

A Quirky Communion of Friends

Palestrina was born to lead the Church’s finest choirs, whether he was too modest to say it or not. His musical pursuits brought polyphonic music to its loftiest height, making it less earthly and more divine–the stuff of angels. Even in his lifetime, his name was legend. He wrote over 100 Mass settings, leading Rome’s greatest voices in song, and even–so some would claim–influencing the Council of Trent’s directives about music in the liturgy.

So what was he doing leading music at a hot, sweaty picnic between stops on a pilgrimage in Rome?

Father Philip. It always came back to Philip and his crazy schemes.

If we could see into Palestrina’s head, we’d probably discover that he didn’t mind this humble task. In fact, the arrogant couldn’t abide Philip for long. Despite his talent and renown, then, Palestrina must have been a humility-seeking man. If not, he wouldn’t go on to be friends with Father Philip for over 40 years–a friendship that only ended when he received Last Rites from Philip and then died in his arms.

That day in the park, though, neither knew what the future would hold.

When the picnic concert ended and the pilgrimage drew to a close, a handful of men retreated not to their homes, but to Father Philip’s cramped quarters above St. Jerome’s. Their purpose was to read, talk, and pray–to honor God for the goodness He possessed in a light only they could see.

Palestrina, Father Philip, Baronius, and the others who assembled in that room found themselves in the company of kindred souls–men with different vocations, gifts, and insights whose sheer variety couldn’t help but increase the others’ faith and demonstrate God’s wonders. From Philip’s gift of gab and mischief to Palestrina’s leadership and ear for beauty to Baronius’ combined passion and obedient heart, the foundations that would become the Oratory were a reflection of Heaven itself–as all good friendships are.

And the more friends in the friendship, the greater the reflection.

How is Friendship a Reflection of Heaven?

C.S. Lewis, who was no stranger to friendship or strangeness–he and Tolkien once showed up to a party dressed as polar bears–says in The Four Loves, “Of course the scarcity of kindred souls–not to mention practical considerations about the size of rooms and the audibility of voices–set limits to the enlargement of the circle; but within these limits we possess each friend not less but more as the number of those with whom we share him increases. In this, Friendship exhibits a glorious ‘nearness by resemblance’ to Heaven itself where the very multitude of the blessed (which no man can number) increases the fruition which each has of God. For every soul, seeing Him in her own way, doubtless communicates that unique vision to all the rest.”

Palestrina’s music has been called heavenly, but was it the notes themselves, or the many voices bringing out the beauty of the others, that makes his music so divine? Was Philip’s Oratory magnetic because it brought men together in faith and fellowship, or because the act of bringing them together brought each man’s essence more clearly into light–revealing God’s essence in the process?

And what about our friendships? Are they treasures because we value them on earth, or because they give us a foretaste of the treasures of Heaven’s own communal life?

Friendship as a taste of Heaven’s own communion. What are we to make of that?

by Giuseppe Passeri

The Link Between Art and Friendship

Creative pursuits at God’s service can make a man’s heart sing, yes. There’s something to be said for the beauty of a lone voice rising in song.

But there’s a reason Palestrina’s multi-part compositions, with their throngs of soaring voices blending in pursuit of one song, are considered a jewel of the Church and are still used today. It’s because two voices are better than one, three are better than two, and a heavenly host better than a single baritone. We were meant for communion, to sing Holy, holy, holy as one–and our communion is meant to invite others to join the eternal song.

It’s not about extrovertedness or introvertedness. Friendship isn’t about sharing words, space, or time together so much as it’s about sharing a vision. Yes, togetherness is part of friendship. But your friends don’t cease to be your friends when they’re out of sight. They haunt your solitary moments, their voices echoing in your head when you imagine their reaction to the news story you’re reading, their smiles flashing through your memory when you hear a joke you can’t wait to tell them. You are joined in this communion of souls, this communion of thought and truth, for as long as you both see that same truth and go after it.

If a) virtuous friendship is a sharing of truth, b) God is truth, and c) we can only see truth if God reveals it to us Himself, then we must concede that we do not make friends. Friends are given to us. They are a gift from God–completely superfluous, “like art,” as Lewis says.

And yet to artists, art doesn’t feel superfluous. When we make music, bring characters to life, or put an idea on a page, we feel most like ourselves. The same goes for the times when we are with our friends.

No, art and friendship don’t feel superfluous. But they also don’t feel as earthy as life’s necessities–not when they’re rightly ordered. Virtuous art and virtuous friendships are imminently spiritual. They’re different than food, drink, and shelter. They’re not basics. They’re too exquisite to be classified as needs.

So what are they?

Art and friendship aren’t necessities but a sign of privilege–an indication of the lofty place God gave to man when He made us in His image. They set us apart from mere creatures. Beavers build dams and gorillas use tools. Dolphins have a sophisticated language. But their structures, tools, and communications are utility, not art. They likewise have companions, but they do not have friends.

To taste friendship is to taste, in a very small way, the splendor of love that awaits us in Heaven, just as art gives us an infintessimal glimpse of the beauty of the world to come. And that makes friendship a treasure.

It makes friendship an art–God’s art. It’s the picture he’s painted of the communal love we are meant to share. It’s the way he draws even those outside the friendship to turn their eyes toward the friendship’s Artist and Creator Himself.

The Friend I Am

So what do St. Philip Neri and his friends have to say to us today? About friendship? Creative pursuits? What can they tell us about art’s power to evangelize and how it’s enhanced by the power of friends?

In all likelihood? Nothing. They would probably look at each other, shrug their shoulders, and say, “I don’t know. We just like each other, I suppose.” (To which Baronius would add, “But I only like Philip if he promises never to mention the wine shop again.”)

No, if we want answers on friendship, we’d do better to turn to Lewis in The Four Loves, or to search for records of such a conversation between him and his friend Tolkien, for that’s the sort of discussion they could very well have had. But it’s no use asking the first Oratorians. They were captured by a different truth.

Perhaps there’s nothing more to say. Perhaps it’s already been said, hidden between the lines of our real-life characters’ stories. Perhaps all this time, as you read these words and I wrote them, we’ve been on a pilgrimage of our own.

And what have we discovered? The evangelizing power of the art we make with friends? New friends in Heaven (for who wouldn’t want to call St. Philip Neri a friend)?

For me, I have discovered that friendship is more than a taste of the heavely communion I will one day share with my fellow man. It’s a sign of the Friend that’s waiting for all of us there, waiting for us at every Mass. It’s a sign of the one Who doesn’t ask, “Do you see the truth that I see?” but, “Do you see the truth that I AM?”