The Catholic Artist & the Culture Fight: Combatting Statue Smashings & Lies with Beauty

- Post author:Katie Lovett

- Post published:September 24, 2021

Yorkshire, England, June 2001

Never in my life had I seen such a massive, hulking beast of a building. The cathedral was enormous. It didn’t just tower, it loomed, its highest spires butting against the clear blue sky as if holding up the clouds. Standing in York Minster’s shadow with my tour group and our guide, I could only gape. How could anyone look at that edifice and not feel the weight of centuries pressing down on them?

I had been 18 for two weeks and a Catholic for eight, my heart full of the optimism of youth and my soul still reveling in the newfound life I had in Christ’s true Church. England to that girl was a marvel. I knew York Minster belonged to the Anglicans now, but I could love it still. I could love it for the centuries of service it had given the Church, could imagine myself back in time, on my knees behind those walls of stone.

And yet…something wasn’t quite right.

Taking a deep breath and working up some courage, I approached our tour guide. He smiled as I stood before him, and I smiled back because he was cute and British. But that wasn’t enough to distract me from my question.

I looked from our guide to the cathedral’s strangely bare walls. “Why are all the statue niches empty?”

“Good eye.” Tipping his head back, he surveyed York Minster, its surface entirely covered with bare stone niches. “It’s simple, really. During the Reformation, the Roundheads wanted to remove any trace of Catholic idolatry. So they pulled down the statues.”

“Pulled…pulled down the statues?”

“That’s right. They smashed them all.”

Those blue English skies might as well have turned their stereotypical gray for me. I turned back to those empty niches, a heavy feeling in my chest. As my gaze swept the spaces that once housed reminders of God’s most faithful servants, I had only one thought.

What ignorance! What hate!

Little did I know that nineteen years later, I would watch St. Junipero Serra’s statue fall and think the same thing.

This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

As the dust has settled in the year since protestors toppled the missionary saint’s statue from its pedestal, many of us are still reeeling, wondering why. What has inspired such anti-religious fervor? Some blame the devil and some the Democrats, but that only speculates on the who, not the why.

The why is important. The who is ever-changing in the age-old struggle between man and his Maker, but the why remains the same century after century, from the anti-Catholic Roundheads to Antifa and their ilk today. So what is the why? When push comes to shove, when you get right down to it, why do the forces opposed to truth target statues, saints, and all our treasures? Why can’t we have nice things?

The reason now is the same as ever. It can be found in the shadow of York Minster’s bare walls and in the echo of voices on a YouTube video of St. Junipero Serra’s statue’s fall.

We can’t have nice things because of ignorance. We can’t have them because of hate.

It would be nonsensical to label every man or woman who ever targeted a Catholic statue as evil without understanding their reasons why. Some, no doubt, are oblivious souls caught up in the fervor of a movement, targeting something they’ve never experienced and know nothing about. Others started out that way…and then those lies festered in their hearts, taking root and becoming vitriol and loathing, the devil’s favorite tools. Either way, ignorance stands at the center of the problem. Either way, the light of truth is the answer.

But how to shine that light?

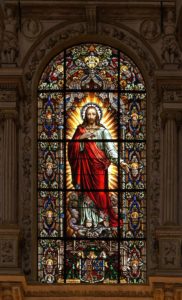

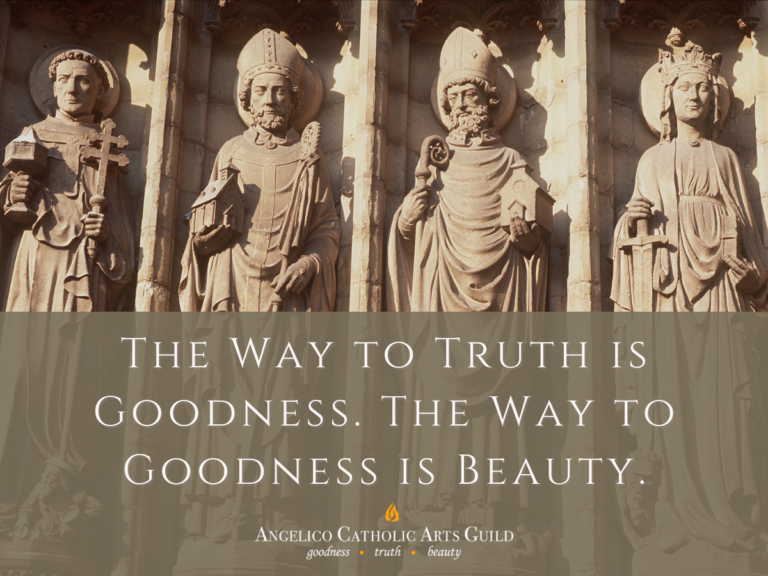

As Catholic artists committed to the three classic transcendentals, you and I understand that the way to truth is goodness, and the way to goodness is beauty. That’s the whole reason we have statues in the first place. Their beauty points us to the saints, who are good; the saints point us to God, who is Truth. That’s simple. Basic stuff. It’s Sacred Art 101. It’s how the Church has spread the faith for untold centuries.

But what do you do in untold times? What do you do when the once-Christian culture rejects a man most humble and raises the Pride flag on high? Is art that’s beautiful, highlights the saints’ goodness, and points to truth enough anymore?

Yes. Yes, it is. But only if we do it right.

So how do we do it right? How do we battle ignorance, bring enlightenment, and put the power of beauty to work in pointing our culture to truth–even as they tear down the beautiful things we make? How do we lead our culture to the Truth that is Jesus?

How do we share the saints’ goodness with a world that only seeks to tear them down?

As always, it starts with fortifying the Church itself.

We’ve Lost Saint Anthony!

Quick–who’s the patron saint of lost things? Easy, right? Every disorganized Catholic knows St. Anthony is the one to turn to when we lose our keys…but why? What else do we know? Shouldn’t this one mundane fact point us to something more exciting?

In most of Catholic America, we’ve lost something more critical than car keys–we’ve lost our knowledge of the saints. And if you think you’re not going anywhere without keys, imagine how long we’ll languish without the saints.

The saints are some of the most powerful witnesses to God’s goodness and truth. Sadly, most Catholics had never heard of St. Junipero Serra until he became the far-left’s favorite target. Optimists might say that at least this incident has got Catholics learning his name, but don’t be too hasty. Because the culture was the first to bring him to the world’s attention, they were the ones who got to set the narrative–for Catholics and the world. Which begs a question.

Why aren’t we doing a better job telling the world–and our own members–about the saints?

Now, I know the automatic response to this. “But we’re already promoting the saints!” And I agree, there’s plenty of saint-themed Catholic art out there in a variety of forms. Maybe the world had never heard of St. Junipero Serra until recently, but it’s not as if the Church and its members aren’t producing saint-centered media. I’d even venture to say that some of it is great. But the bulk of these saint-based works? Let’s be honest. No one–not even faithful Catholics–cares a lick about them.

Because they’re not good. They’re well-executed, but they’re not engaging.

And if people don’t care about the saint stories we tell? They won’t read or watch or listen. If they don’t read or watch or listen, they won’t learn. They won’t learn the lessons that our forefathers in the faith can teach us. They won’t be transformed–and they won’t pass these lessons on to the world.

Oh, St. Anthony. Help us find our lost saints.

Unleashing the Beauty of the Saints

If telling the saints’ stories isn’t enough to educate the faithful about the saints, then what is? Simple. We need to tell their stories in beautiful ways.

But how? Why?

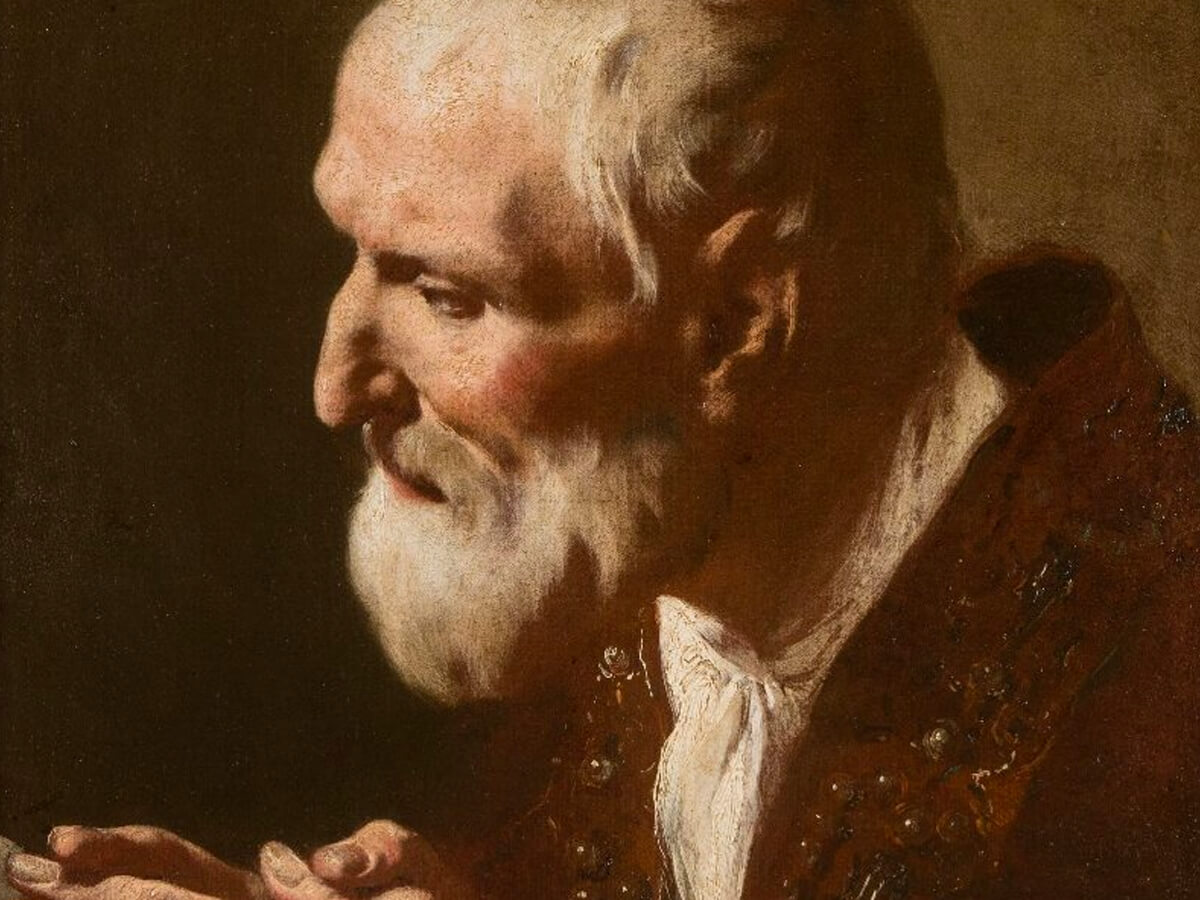

Why must we tell the saints’ stories in beautiful ways? Because beauty is the soul of truth. If we were purely spiritual beings who lived outside of space and time, beauty and truth would be nearly indistinguishable, impossible to separate. But here in the material sphere, things are different. The facts by themselves aren’t enough to hold us spellbound. If they were, then any truth-filled textbook would be riveting, never mind that it’s as dull as a sack of turnips. It wouldn’t matter.

But it does matter. It matters because the truth, for mortal man, does not come alive unless we can see its beauty. Beauty is what breathes truth into life.

The saints are beautiful. The saints are fascinating! Why have we made them so boring? Why have we made them so inaccessible? Isn’t anyone tired of those trite novelizations of saints’ lives written in saccharine sweetness without an ounce of soul or heart? It’s no wonder the only time a kid touches these books is when she pulls them out of a First Communion gift bag.

And what about saint movies? Why–with a few notable exceptions–are they only in Italian? I happen to like some of them, but subtitled movies are useless in passing on the faith to my dyslexic son. Between 5 and 15 percent of the population is dyslexic, and even those who aren’t have little interest in a movie they have to read. Doesn’t anyone who speaks English know how to make movies?

If beauty is the weapon we must use in the fight for truth, and if we must keep this powerful weapon from falling into the wrong hands, we cannot let the culture tell more compelling tales about the saints than we do. No one will care that the culture’s tales are lies and ours are truths if the lies look pretty and the truth looks boring.

So how do we do it? How do we harness the power of beauty to unleash the saints’ witness on our Church–and on our broken world?

Every Catholic Artist Must Be an Iconographer

If we want to change course, make saint-based art that’s faithful and engaging, and exchange the culture’s hostile takeover for the Church’s holy one, Catholic artists cannot just be artists. They must be iconographers.

Now, I don’t mean that literally, of course. What I mean is that the mission of the icon writer is, in a sense, every Catholic creative’s mission. Why? Ironically, it’s a Loyola Press article’s explanation of what icons are that gives us the reason:

“Religious icons are…representations of a greater ‘object,’ but in this case, the ‘object’ is a person…Icons are like quick links in that they give us a kind of symbolic snapshot of holy persons who are in heaven. More than that, religious icons are a form of prayer…Icons, then, are not just art with a religious theme; rather, they are sacred art because they bring the viewer to the sacred.”

Does the Church’s current, mainstream stable of saint-based media direct viewers to the sacred? Not when we’ve gutted their stories and left out what matters. We’ve directed viewers’ eyes, all right–to saints made by our hands, not by God’s.

Do the majority of saint movies, children’s books, and curricula provide snapshots of the saints? Or do they provide Picasso-like images–distorted depictions that make it impossible to recognize the person they symbolize?

Does the current standard of Catholic media represent greater objects? Or do they represent lesser, watered-down ones?

It’s a harsh assessment, I’ll grant you that. But we as Catholics have to face the fact that what we’re doing isn’t working. We won’t win hearts in the culture or the Church if we peddle saccharine sweet saints, only promote the useful things they patronize, or just honor saint quotes that look good on social media and can be twisted to mean whatever we want.

Let’s Get Our Nice Things Back!

It makes little sense to battle the culture’s distortions of the saints with distortions of our own, but that’s exactly what we’ve been doing–and that’s why we can’t have nice things.

Or can we?

If we want to turn this ship around, it’s going to take time, but eventually, we can put an end to the culture’s attack on our saints. Probably not in our lifetime, but this is where it starts. You and I, my fellow Catholic artists, must be the founders of a movement that stretches into the ages–a movement that holds the saints up as beacons pointing the way to God Most High. That movement begins with a change in perspective.

Those who make subpar saint-based works aren’t short on talent, but on vision. Our vision must be iconographic, not propagandist. We are here to represent the saints in all their potency, not pull out the convenient bits we think people want to hear..or even just the things we want them to hear. We must use beauty when we share the saints, and we must share them in all their fullness. We must use beauty to bring knowledge of the truth.

The ignorance must stop. Only then will the hate fall. Only then will our statues live on.